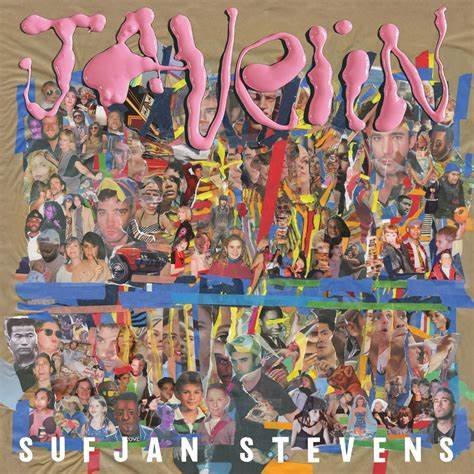

Unearthing The Past And Pondering The Future In Sufjan Stevens’ Javelin

I first learned that Sufjan Stevens was releasing Javelin on August 14th, 2023, while emptying my bedroom in New York City and preparing to pack for Kenyon. I decided that a new Sufjan album, let alone his first “folk singer-songwriter” album since 2015’s Carrie and Lowell, was some sort of sign from the universe that my first semester at Kenyon wouldn’t be quite as daunting as I had made it out to be in my head. I was right; Javelin exceeded my expectations. Sufjan Stevens’ return to the type of music that initially catapulted him into mainstream consciousness was one of my favorite things that unexpectedly happened in 2023.

In Javelin, his latest release through Asthmatic Kitty Records, Stevens knows where he excels: in abstract yet somehow extremely concrete and tangible storytelling. Stevens’ fans, including myself, all revel in his ability to create narratives and universes in his songs that are larger than life. The characters in his universe slowly become the characters in ours if we only imagine enough. You know you’re listening to Sufjan Stevens when you can see yourself so clearly in all his settings (even if you haven’t been there) and in all his characters (even if their experiences have been so radically different from yours). In Javelin, much like in Carrie and Lowell, Stevens takes a slight departure from the fictional Midwestern mythos that helped him become a household name in indie-folk and writes about his own experiences with loss, conflict, isolation, and undying hope.

When posting about the album on release day, Sufjan announced the April 2023 passing of his long-term partner, to whom the album was dedicated. Stevens’ experiences of grief and love are reflected in Javelin, whether alluded to directly (“Javelin (To Have And To Hold)”) or more subtly implied as the subject of a song (“Goodbye Evergreen,” “Shit Talk”).

Javelin begins with “Goodbye Evergreen,” a heartbreaking farewell song in which Stevens is determined to tell his lover how he felt about him, although “something just isn’t right” inside in the wake of his loss.

“A Running Start,” one of the singles off of the album and the second track, gives us a brief glimpse into the reverie that was Stevens’ life before his grief. This song exemplifies the artist’s ability to transport the listener into his universe through production and lyricism. His use of soaring instrumentals and ambient, harmonic choruses give listeners an entry into the narrative world he has spent his whole career crafting. Perhaps the most special part of Stevens’ lyricism throughout Javelin is the sprawling life that it creates in our minds as we listen; he is not just on the fire escape, his “body moves in twisted ways”; he did not hurt his lover, he threw a “javelin right at [him]” (in “Javelin (To Have and To Hold)”) and is left to reflect on his unshakeable feeling that he is the reason that it all went wrong.

On the album's third song, Stevens asks a universal and vulnerable question to the world – one that we have all wondered at different times and in different contexts and one that it can feel comforting to hear your favorite indie stars ask: “I really want to know Will anybody ever love me? / For good reason, without grievance, not for sport?” Sufjan sings this in a light tenor. In Javelin, this question occurs repeatedly. The 48-year-old singer-songwriter has always asked these probing questions in his music, but they have never been clearer or more inextricably linked to himself than they are in Javelin. Early on in his career, Stevens was loved for writing a specific type of narrator, oftentimes a simple Midwestern teen understanding that their family members are fully human, that loss can feel a bit too grand to put into a song, that we have things in common with those that we are most scared of, and that the mundane can feel sacred. Now, he is no longer such a character; he is no longer “thinking outrageously” (as in The Predatory Wasp of the Palisades…, 2005) but rather facing himself as clearly as ever. He is unafraid to ask for support, pleading “hold me tightly lest I fall” in “Shit Talk” and admitting that he “drinks til [he’s] lost” in “My Red Little Fox.”

The theme of finding peace, vastness, and rest in tumultuous circumstances is reflected in Javelin’s production. In “So You Are Tired” and “Everything That Rises,” Stevens ends the songs with a meditative orchestra of voices and instruments, seemingly taking a reference from earlier works of his like “Blue Bucket of Gold” from 2015’s Carrie and Lowell.

A review of Javelin would be incomplete without a more in-depth analysis of the album’s eight-minute magnum opus, “Shit Talk.” “Shit Talk” summarizes everything I love about Stevens’ music – his ability to keep listeners engaged up until a shocking but still, somehow, smooth climax (a hallmark of his early works, specifically the songs off Illinoise); his ability to communicate some of the most profound feelings that occur in relationships that we struggle to articulate until we hear him sing about them; and his subtle but creative references to his previous eras of artistry.

Many of the songs on Javelin sound like they could fit on Carrie and Lowell, but, there is a new element of hopefulness and future-orientation in Stevens’ writing now, even amidst his fresh and recent loss, that contrasts with the nostalgic writing in Carrie and Lowell. In Javelin, Stevens’ allusions to his past, while prominent, are far less vivid and are coupled with more questions about the future. Stevens seems to be reminding himself – and us – that we can still feel the feeling that he once claimed (in his 2015 acoustic ballad Eugene) was behind him. If Carrie and Lowell is a retrospective on the best years left behind, Javelin reminds us that amidst unmanageable grief, the whole world is brand-new and we have only scratched the surface.